Let’s get talking

Language development is core to much of the work that Thrive at Five supports in its programme areas – and with good reason.

The case for a focus on early communication and language is so powerful that it has become a key part of governmental strategies across the UK.

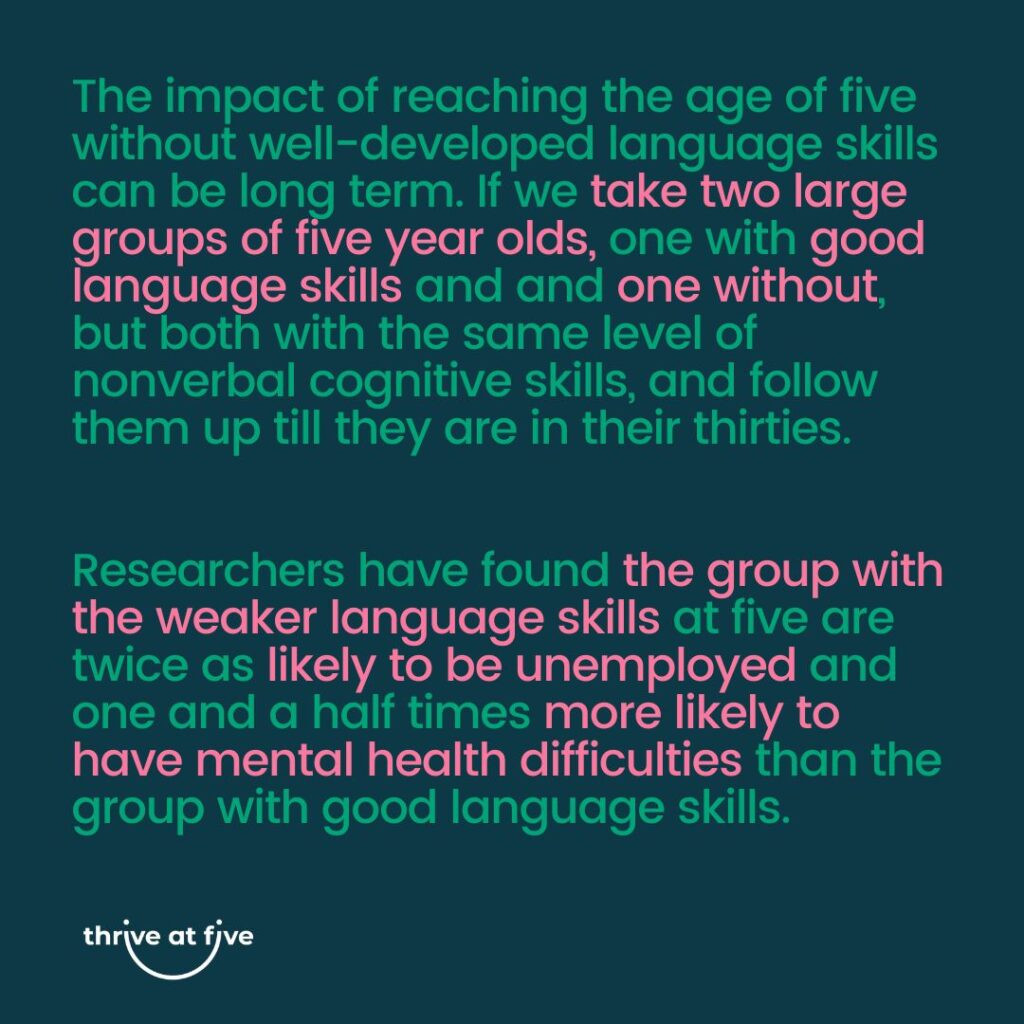

It emerges again and again as a key school readiness concern amongst school leaders. It is closely linked to disadvantage; research with the ‘Millenium Cohort’ found a gap of 16 months between the vocabulary of children brought up in poverty and the vocabulary of better-off children, at the age of five. The gap for non-verbal skills was not nearly as wide, and the gap in the UK seems to be much larger than in countries similar to our own.

‘Of all the socio-economic inequalities in child health and development’, say expert researchers Sheena Reilly and Cristina McKean ‘none is larger than those related to language’.

The national policy landscape

Because of findings like these, early language has become a focus of substantial work by combined NHS and government education departments across the UK.

In England, the inclusion of a target to increase the proportion of five year olds achieving a good level of development within the core missions of the current government has notably sharpened minds. Regional support teams will be asking local authorities questions about their data, support will continue to flow into programmes like the Nuffield Early Language Intervention (NELI), and there is funding for innovative partnership projects, like one working in GP practice areas in north London to provide a home visiting programme for new parents that has both secure attachment and early language and communication development at its heart.

All the while, the DfE and NHS in England have continued to work with experts in communications and marketing to deliver a parent-facing campaign, originally called ‘Hungry Little Minds’ (now subsumed under the NHS ‘Start for Life’ brand), aimed at encouraging parents to chat, play and read with their children.

The Welsh government has a similar ‘Talk with Me’ programme which involves awareness-raising, workforce development and an ambitious commission for a suite of early identification and intervention tools. Significantly, there has been long-term Welsh government investment in early language through its flagship Flying Start programme which provides enhanced health visiting, funded childcare for two-year-olds, and parenting and speech and language programmes for families living in the most disadvantaged postcode areas.

In Scotland we now have a National Language and Early Communication project (NELC) which aims to connect people in a shared effort to nurture early communication skills – to make early language ‘everybody’s business’.

What works in early language development?

While governments and other agencies are attempting to support parents through national campaigns, evidence suggests that messaging alone is not enough. Research has shown that what works best are communications that are personalised and phone-based – for example, sending families carefully chosen videos that show interaction strategies that are just right for their child’s age and stage , and to which they can respond – for example by uploading videos of themselves using strategies when interacting with their child.

Messaging also works best when mediated by trusted, local adults – such as health visitors, nursery practitioners and school staff.

One such initiative was at Spring Gardens Primary in North Tyneside, where the headteacher applied for a grant to try to address the exponential rise in children coming in with little ability to listen and attend, have a conversation or persist with activities or try new things. Staff worked with parents and their nursery or Reception-aged children over a series of three play-based, two-hour sessions designed to increase the quality of parent-child interaction. Session 1 focused on outdoor and table-top games. In Session 2 families cooked a savoury and a sweet dish and in Session 3 they made a figure using woodwork tools. Parents were tempted in with the promise of a goodie bag they would get to take home after each session, such as a set of cooking utensils. Each time, there was an activity to do at home, based on what had been modelled in the session. Children were given a booklet of prompts and photos they could use to explain to others at home what they had been doing in school.

At first parents themselves found it difficult to speak and listen, and really struggled to put their phones away for two hours. But over time they became engaged and there were visible changes in the children’s ability to concentrate rather than ‘flit’ from one activity to another, as well as marked changes in the adult-child relationship.

Swimming against the tide

The story of Spring Gardens brings home the societal challenges we face in trying to improve children’s communication and language skills. New research is showing that the time our young children spend on screens is actively damaging their language development. A study in Australia found, for example, that the more screen time a child has between the ages of 12 and 36 months, the fewer child vocalisations were recorded, the fewer adult-child conversation took place, and the fewer adult words the child heard.

So much, so obvious. But what troubles me is the effect of the amount of time adults are spending on their phones. We know from one important study, for example, that two year olds’ vocabulary and early sentences were negatively associated with the extent of parents’ use of digital media during routines like mealtimes, getting ready for daycare or bedtimes. Mothers’ phone use has been found to be associated with a 16% decrease in the speech output of four month old babies.

Phones get in the way of what matters most for children’s language development – back and forth conversations with responsive adults. A classic study found that for every extra 11 such back and forth ‘turns’ at home, there was a one point increase in a child’s score on a language test. And brain imaging in the laboratory while stories were read to the children found that having lots of such conversations at home was directly associated with increased activity in the part of the brain that manages language. Conversations do indeed light up the brain.

So what are the next steps?

We need, of course, to get the message across to families that putting the smart phone away, having conversations with children and sharing lots of picture books with them will give them the best possible start in life. But we can’t do this effectively by lecturing people, being ‘experts’, or imposing programmes that have worked somewhere else but may not be right for particular communities.

Much more likely to succeed is the Thrive at Five model of working in partnership with parents and communities to co-design new initiatives, and connecting families with trusted local ‘Parent Connectors’ for support.

More likely to succeed, too, are approaches that upskill all those who work in the early years in nurseries and schools in high-quality, language-enhancing practice. The recent and continuing expansion of government-funded childcare places in most of the countries which make up the UK makes this especially important.

Here too, Thrive at Five has been ahead of the game, through its ‘Talking Time’ programme in nursery classes and the NELI programme in schools.

It was a privilege to hear about approaches like these at Thrive at Five’s recent conference on early language, held in Stoke on Trent, where I shared some of the ideas in this blog.

It was a great day, and I’m looking forward to seeing this work expand across the UK in the future.

Jean Gross CBE is the former government Communication Champion for children, and a member of Thrive at Five’s Advisory Group. Her book ‘Time to Talk’ (2nd edition) is published by Routledge.